——————–

When I began my two-year journey around the world, I knew I’d go to Vietnam for sure. It would be my second time there, and I’d end up making it my home base for seven months.

But Malaysia? That was totally unplanned. And as with nearly all things unplanned, traveling through Malaysia became one of my favorite, most memorable experiences.

And the journey to Pulau Tengah was the highlight.

What’s so special about Pulau Tengah?

Pulau Tengah is a small uninhabited island in the South China Sea located off the southeast coast of Malaysia.

From the late 1970s until 1981, it served as a UN refugee camp for thousands of Vietnamese “boat people” escaping the communist government.

Photo courtesy of RefugeeCamps.net

My parents were among those “boat people.”

How did my parents end up on Pulau Tengah?

Here’s the short version, which my parents gave me growing up:

- We and a bunch of other people hopped on a stolen boat.

- We sailed south towards Australia.

- We came upon a refugee island called Pulau Tengah and we stayed there til we were sponsored to the US three months later.

- The end.

I used to wonder if my parents had some level of PTSD and that’s why they didn’t give me much detail about how they came to America. But in reality, it’s that their escape was relatively easy and drama-free. My parents had always been very humble about their escape from Vietnam, always diverting attention to someone else’s incredible story.

“Oh, you wanna hear a real survival story, you should talk with so-and-so,” or “Our escape was really easy, you know so-and-so didn’t have it so lucky.” I suspect a bit of survivor’s guilt.

In the last several years, my parents have opened up a lot more. My dad especially – always the nostalgic, sentimental one – loves to reminisce. Drama or no drama, guilt or no guilt – this is my parents’ story:

It was 1978. Mom and dad were not yet an item. In fact, my mom tells me she couldn’t stand my dad at the time, haha. He was vain and arrogant, she says. (This cracks me up, as we all know the type of person my dad turned out to be!) They were both from the countryside (dad from Võ Đắt; mom from Gò Công), and had moved to the city six years earlier to get an education.

Both of them happened to be living with my mom’s sister (my Aunt Hai), her husband (my Uncle Côi) and their five young children (my cousins). Mom was in high school while also helping to take care of her sister’s house and kids. Dad was a close family friend and a guest in the home whenever he came to the city.

It’d been three years since the Fall of Saigon. They’d survived the war, and they’d been living under communist rule ever since.

Dad, the free-spirited 20-something bachelor, had tried to escape the country many times without success. A fisherman’s family repeatedly promised him an out – “We can get you on a boat, we just need this much money/gold from you” etc etc. My dad and his friends would give them everything they had. But each time, the fisherman’s family made convincing excuses not to go. Tonight’s too risky after all. Or we’re gonna need more money from you to make the trip.

Basically, my dad spent two years getting swindled by this family. Rumor has it, that family later ended up in California. I’d love to march up to their front door, and be like, yo! Dude. WTF?! But dad doesn’t seem to hold a grudge. He’s not the type. I’ll hold it for him, haha.

It was in the wee morning hours of March 28, 1978 that my dad and the rest of the household managed to escape.

But first, the fact that my dad was a part of the group that night was a bit of a miracle. Weeks earlier, his ID had been confiscated by a police officer who didn’t like my dad’s hair.

“Your hair is too long. Come back when you get it cut, and you’ll get your ID back.” (That was life in Vietnam at the time, can you imagine?!)

My dad got his hair cut as instructed, but was unable to recover his ID. With no ID, travel between regions was very challenging. You had to have your ID to get the equivalent of a “permission slip” to leave a region for another. My dad was in the countryside and was desperately trying to go to the city. If he was to leave the countryside, he would have to sneak his way out.

In and of itself, the urgency my dad felt to leave for the city that day was uncanny. Normally, when he went home to visit his parents in the countryside, my dad would stay for the entire duration of his permit. But something unexplainable was pulling him to the city instead.

My dad took a chance and hopped a cargo train to Saigon. With no ID and no permit, my dad lucked out in that not a single officer came by to check passengers. My dad suspects it had something to do with the government’s anti-comprador bourgeoisie /anti-capitalism movement, which at that time was focused on stopping the transport of merchandise rather than passengers. Whatever the case, my dad arrived in Saigon without a hitch.

And as chance would have it, he arrived in Saigon to find out from my Aunt Hai that there’d be an opportunity to escape Vietnam the next day.

This must be what was pulling my dad to the city. The universe had spoken. But my dad was not prepared for this. And neither was anyone else. That’s the way it was. If you were told you had an opportunity to leave Vietnam, you took it. That week, that day, that hour, that minute. Whatever moment’s notice you got, you were gonna go. Period.

While everyone prepared themselves and their families to flee the country, my dad had two orders of business:

- Paying off his open tabs at a few coffee shops in the city. This was common in Vietnam – young single guys hanging out at tea/coffee shops and accumulating a tab that was casually paid at their leisure on an honor system. There was no telling if he’d ever return to Vietnam, so paying the local shop owners what he owed them was my dad’s top priority.

- Obtaining a permit to leave Saigon for the Mekong Delta the next day where the escape would take place. Again, without ID, this was extremely challenging. He paced the ticket office, discreetly waiting for a friend who worked there and could hook him up with a permit, but she never showed. He would have to risk going without the permit, and again, count on a lucky ride out of town, undetected.

Everyone had their own priorities, of course, and loose ends to tie up. But one thing they had in common: they did them quietly. If word got out that anyone was attempting to escape, everyone risked being arrested (or worse). There were no going-away parties, no proper goodbyes. You couldn’t even pack a backpack because it would look suspicious.

You left with the clothes on your backs and not much else.

The Escape

My mom, my Aunt Hai and her five young kids left the city by bus and headed to Cần Thơ, a city on the Mekong Delta. My dad took a different bus there, and as luck would have it (again!), he arrived without ever being checked for ID or permit. The stars really aligned for my dad to escape that day.

In Cần Thơ, they were among 150 people to hide in various shelters along the river bank. My mom and her sister’s family hid inside a shed behind someone’s house. My dad hid in a brick factory building nearby.

They hid for hours in silence, from early afternoon into the darkness of night, waiting for their escape boat.

Meanwhile, my Uncle Côi was notably absent. He was busy trying to prepare that escape boat…

…by HIJACKING it!

Uncle Côi was chief mechanic on a large fishing boat. He conspired an escape along with five other crew members (including the captain) and the plan they hatched up was this: they would take over the boat, load it up with loved ones and leave the country.

What was tricky about this was there were five other crew members who were NOT in on the plan – they were communist officers. They were the enemy. And they were armed.

When the communists took over in 1975, many major fishing boats became government property. Any trips made on these boats were watched over with armed officers. For these five particular officers, this was supposed to be an ordinary night setting sail with the crew for a month-long fishing trip. They’d done it several times before.

Only, unbeknownst to these communist officers, tonight they would be getting super drunk, disarmed, tied up with rope – and they’d be leaving Vietnam.

For them, the evening started out normal enough. All 11 crew members worked together to load the boat with supplies (normal). There was 30 days’ worth of food, water, ice, fishing supplies and fuel (normal). When they finished, they left the dock to sail down the Hậu River (normal), and decided to anchor the boat for a bit so everyone could sit down and enjoy some whiskey and cognac (again, normal).

What wasn’t normal was that my Uncle Côi and his co-conspirators were actually drinking tea from the strategically filled liquor bottles while the five officers were throwin’ back hard alcohol. When the officers got good and drunk and nearly passed out (normal), Uncle Côi and the guys took advantage of the situation. They took their weapons, and they tied the officers up.

The officers were so drunk, there was no struggle. It was almost too easy. But my uncle and the rest of the crew weren’t out of the woods yet. They still needed to get 150 people onto the boat and leave the Mekong Delta unnoticed.

At this point, everyone waiting just off the river bank had been hiding for several hours, clueless as to what was happening on the boat. It seemed like an eternity, knowing they could be caught at any moment and brainstorming what they’d do if the police showed up. It was unsettling. Tummies were growling, hearts were racing. The fear was consuming. Children had to be consoled and anxiously hushed so as not to blow their cover. Some were even given cough medicine to make them drowsy and keep them from crying.

After the officers on the boat were tied up, word spread that it was time.

Everyone in hiding came out of the woods and onto the river bank to board the boat as quickly – and as quietly – as possible. It was absolute chaos. The original plan was for everyone to paddle out to the boat in canoes, but instead, the boat ended up coming right up to the river bank in shallow waters. There was some struggle preventing the boat from getting stuck in the mud, but this also made it easier for people to climb straight up into the boat.

As everyone came out of hiding to board the boat, my Uncle Côi eagerly looked around to make sure my aunt, their kids and my mom were among them.

They weren’t. His family was nowhere to be found. This was NOT ok.

He went to one of his co-conspirators and said something to the effect of, “If you mother f*ckers even THINK about leaving my family behind, I will blow the lid off this so fast and NONE of you will be leaving Vietnam tonight. GET my family. NOW!”

Ok, so those probably (definitely) were not his words. But you get the idea. This was a life and death situation, and my uncle meant business. With one of the officers’ stolen guns in hand, Uncle Côi pointed to the sky and said, “You have until I count to 10 to get my family on this boat.”

It worked. Eventually, my Aunt Hai and the kids, my mom, my dad, and everyone else who was supposed to be on the boat was accounted for – chaotically, but assuredly. My cousin Nhi, who was seven years old at the time, remembers being picked up and passed hastily from person to person through an assembly line to get her on the boat.

With all 150 people aboard, the escape boat – the “Côn Đảo 3” – was ready to go. Only, the boat had come too close to the bank and was stuck in the mud! The captain had no choice but to gun the engine. This escape was going to be loud. REALLY loud. The chances of getting caught rose exponentially in those few seconds.

But despite the deafening sound of the gunning engine, the Côn Đảo 3 managed to get out of the mud and sail down the river undetected.

They sailed in darkness down the Mekong distributary and out into the South China Sea. The Côn Đảo 3 was a large, multi-tiered boat. My mom and her sister’s family were housed upstairs in the captain’s quarters. My dad climbed onto the deck above so as to avoid the main cabin below which was extremely crowded.

A few hours later at sunrise, they were met with still waters, sunny skies and even the occasional dolphin. Dolphins! My dad remembers sitting on the top deck of the boat, watching the majestic creatures leap to and fro, while marveling at the fact that he’d finally done it – he left Vietnam!

And it was smooth sailing. My mom tells me sea sickness was as bad as it got for them on the Côn Đảo 3 – people were constantly vomiting over the side of the boat. But all things considered, this was a small price to pay for their freedom. For other boat people, thirst and starvation were a huge risk, as was inclement weather or getting robbed (or worse) by Thai pirates. Getting caught was always a frightening possibility. My dad tells me up to one half of the boat people attempting to escape in this time did not make it. There was no telling what fate awaited them at sea.

Nevertheless, my dad says the crew was ambitious and overconfident – they planned on sailing all the way to Australia!

Although successful escapes to Australia weren’t unheard of at the time, this journey on the Côn Đảo 3 was destined for something else. After three days at sea, they approached another boat to ask for directions, and were informed that there was actually a refugee island close by called Pulau Tengah.

Out of curiosity, the crew steered the Côn Đảo 3 towards this refugee island. As they approached Pulau Tengah, a beach full of Vietnamese people gathered to greet them, waving excitedly and beckoning for them to join them. A couple guys got into a canoe and paddled out to convince them to stay.

There’s water, there’s food, they said. The UN is here, and we’re being treated well. Every day, more and more of us are being accepted into countries all over the world. Why sail to Australia, when you can FLY there!

These guys were pretty convincing. And the island did appear to have a nice set-up. The crew took a chance and agreed the boat would stop here. The fate of my parents and everyone else on that boat would be decided here on this island: Pulau Tengah.

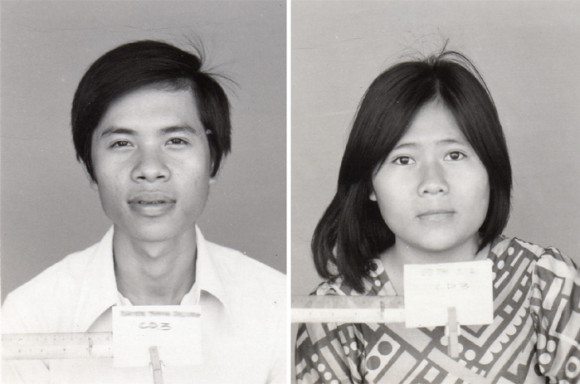

UN refugee registration cards from Pulau Tengah

What was life like on Pulau Tengah?

My parents lived on Pulau Tengah from March 31 to June 23, 1978 – just barely three months.

At that time, there were seven or eight main shelters at the camp, side by side on the beach. Some of them can be seen in the background of this photo below. The camp would grow and the shelters would become more elaborate in the years that followed. But this is how my parents remember the camp:

Photo courtesy of RefugeeCamps.net

The shelters were basic: straw roofing held up by wooden poles. Long wooden planks that ran the length of the shelter were the “beds,” and you just got in where you fit in. You were assigned a plot of wood and that was your space.

Aunt Hai tells me she worried about bed bugs, so she made hammocks out of fishing nets for everyone to sleep in instead.

My cousin Tuan (11 years old at the time) tells me that on the first night, he slept out on the beach because the sand was much cooler and more comfortable. Pulau Tengah is a tropical island, and nights at the camp got really hot – sometimes unbearably hot. Dad tells me he did the same, but for a different reason – there wasn’t room in the camp for him. It was such a common sight to see refugees sleeping everywhere that others on the beach would just step around you as you slept.

Food was provided but everyone was responsible for preparing it themselves. Kitchen areas were equipped with oil burners and other supplies to cook with. Every day, a boat from the Malaysian mainland came to deliver fresh foods, and once a week, it came with dry foods like rice, ramen and sugar.

Five days a week, they were given fish. Twice a week, they’d get chicken or beef (no pork, since Malaysia is a Muslim country).

Sandwiches were provided occasionally, and my parents tell me these were quite a treat. They’d never eaten regular white bread before. Even though all they had to put in their sandwiches was butter and sugar, they tasted amazing. In fact, my mom tells me they ate better on the island than they had back in Vietnam. The food at the refugee camp was basic, but to them, it was glorious!

Soda was a huge treat as well. My dad remembers he got to drink one Coca Cola during his time on the island. Mom was a cutie pie, so boys were happy to share their sodas with her any time, haha.

For refugees who somehow managed to get to the island with gold and US dollars (the two most universal currencies at the time), it was commonplace to pay the locals to pick up luxuries from the mainland such as boomboxes, batteries and cassette tapes to enjoy on the island. Soccer balls, volleyballs and badminton nets could be found around the island too.

Day in and day out, it was mostly a waiting game on Pulau Tengah. Waiting to be interviewed by various countries, waiting to find out if a country had accepted you. Just waiting.

Eating, sleeping, swimming, socializing…waiting.

There were island dramas of course, from heavy political to cutesy romances. For instance, what did you do with communist officers who were tied up and taken to the island against their will, like the five guys on the Côn Đảo 3? They represented everything that these people risked their lives to flee from. You couldn’t exactly keep them with the general population – these guys would probably be beaten to a pulp. They had to be held on a separate part of the island near the police quarters. Some eventually returned to Vietnam; others wound up getting sponsored elsewhere. One group of communist officers even left the island on the Côn Đảo 3, and made it to Australia after all! Rumor has it they went to the Vietnam Embassy to find their way back home to the motherland.

On the lighter side, mom likes to kid my dad about what a ladies’ man he was on the island. Dad, with his scrawny arms and hippie long hair, wearing his bell-bottom jeans. Haha! He was a musician after all, and the girls just loved to crowd around and fawn over him when he played the guitar.

But mom had her share of admirers too. She was only a teenager at the time and had grown up really sheltered. She says she was quite chubby then too, so she was completely oblivious to how much attention she was getting from the boys.

In fact, it wasn’t until months later she learned that one of my uncle’s co-conspirators had only participated in the escape plan because he was promised my mom’s hand in marriage if they made it out of Vietnam! When they got to the island, and this guy realized it was just a ploy by my Uncle Côi, he was an angry dude. Like, violently angry. But that’s a whole ‘nother story!

Here’s my mom with yet another admirer on the island. This guy was the older brother of a girl my mom had befriended on Pulau Tengah. His name was Tuan. And he wanted to hold my mother’s hand.

So cute, right?!

Can you imagine all the stories that came out of this island? The UN ran this refugee camp for probably half a decade, and it’s estimated that 100,000 refugees passed through here. When my parents were on the island, there were probably 1,000 people, and on any given day, there would be more boat people arriving.

Whenever a boat approached Pulau Tengah, everyone on the island would come ashore to greet the boat and eagerly look to see if any of their loved ones were on it. My parents tell me there were many surprising reunions between people who’d been separated during their escape or had simply left Vietnam without being able to say goodbye to anyone.

Many people arrived on the island sick, sunburned and fatigued from their journey at sea. But to show up on a random island and be reunited with loved ones they thought they’d never see again…it was pretty incredible.

Likewise, there were boatloads of people leaving Pulau Tengah as well.

Refugees were being accepted into countries all over the world, including France, Switzerland, Australia, Canada, Germany, even Iceland and Brazil. My dad recalls hearing about someone being sponsored to Israel. Man, what would my life be like had I been born in Israel?!

AMERICA was the golden ticket though. Everyone wanted to go to America. But the US couldn’t take everyone. You had to be interviewed and rejected by at least one other country before the US would even consider you.

Australia was an obvious choice, as it was their original destination. It also seemed that refugees sponsored to Australia were processed more quickly and more frequently, and were able to leave the island much sooner to start their new lives.

However, Australia rejected my whole family.

- My mom, Aunt Hai and Uncle Côi were interviewed as a family unit. When asked if they had family members anywhere outside of Vietnam, they mentioned my Uncle Tuoi who was rumored to be in California. In coordinated efforts to keep families together, Australia rejected the family and had them interview with the US instead.

- My dad interviewed separately and was also rejected. Australia was looking for families, or at the very least, strong, fit men (presumably for farming and laboring). My dad was single. And at five feet, five inches, and barely 115 pounds, he didn’t fit the bill. He, too, ended up interviewing with the US.

Fortunately, the US accepted them all, and sent their information to various refugee aid organizations throughout the country. It was the First Baptist Church in Lacey, Washington that would sponsor them, where a kind and generous churchlady named Fern Powers would take them in. Soon after the US accepted them, my parents, Aunt Hai, Uncle Côi and my cousins would all be taken on a boat to the Malaysian mainland on June 23 to have medical checks in Kuala Lumpur. They would then be processed for entry into the US, arriving July 6.

But first, they had to say goodbye to Pulau Tengah.

Goodbyes were a frequent and bittersweet occurrence. Spending 24 hours a day on an island with people who lived through the same war, suffered under the same communist rule, shared your same fears, uncertainties and excitement about what the future held – it was a special bond. And saying goodbye was never easy.

Many goodbyes were forever-goodbyes.

The night before anyone was set to leave Pulau Tengah, friends would gather on the beach with a campfire, eat chè (a Vietnamese dessert of mung beans and coconut milk), play guitar and sing songs. The song “Biển Nhớ” was the most appropriate song with which to bid adieu, and it became widely known as the farewell song on Vietnamese refugee camps all over the South China Sea and beyond.

The lyrics start off:

Ngày mai em đi, biển nhớ tên em gọi về.

Tomorrow you leave, the sea will call your name.

Here’s the first photo of my family in the US, at the San Francisco Airport:

Dad on the left, mom on the right, Uncle Côi in the middle, and my cousins (clockwise from the top): Giang, Tuan, Nhi, Truong and Quan.

Aunt Hai isn’t in the photo because she had been left behind due to an error with her medical check-up in Malaysia. But she would join the family in America, safe and sound, six weeks later. How she made it to Washington by herself is a pretty neat story too!

Fast-forward thirty-two years: I was about to see Pulau Tengah and this piece of my family history with my own eyes.

How did I end up in Malaysia?

It was 2010. I’d left the US and had been backpacking around Australia. My travel visa was about to expire, and I was low on funds (Australia is suuuper expensive). I had no idea where to go next, so I looked up some budget airlines and picked the cheapest one-way flight I could find out of the country:

- Airline: Air Asia

- From: Melbourne, Australia

- To: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Price: $308 AUD

Done. I couldn’t even point to Malaysia on a map at that time, truth be told. But I was gonna be there in 8 hours and 15 minutes.

And I ended up staying there an entire month. I LOVED Malaysia.

When my parents found out I was heading there, they emailed me, suggesting I visit Pulau Tengah if I had the chance. It went straight to the top of my to-do list.

And thus the journey began.

How do you get to Pulau Tengah?

I wish I had known this at the time, but getting to Pulau Tengah is as easy as 1-2-3:

- Fly to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia –OR– Fly to Singapore.

- Go to Mersing. Here are a few options:

- Fly from Kuala Lumpur to Johor Bahru (1 hour) + take a bus to Mersing (2 hours).

- Take a bus from Kuala Lumpur to Mersing (5 hours).

- Take a bus from Singapore to Mersing (4 hours, depending on how long it takes to cross the border).

- • • • If you’re coming from Vietnam, you can take a cheap, direct flight on Air Asia from Ho Chi Minh to Johor Bahru (2 hours) + take a bus to Mersing (2 hours).

- Charter a 1-hour boat to Pulau Tengah.

If only someone had told ME back in 2010 just how easy this was…*sigh*

Why was it so hard for me to get to Pulau Tengah?!

It seemed an impossible mission. In 2010, there was zero information on how to get to Pulau Tengah. Neither Google nor any other website could tell me how to get there. My searches always turned up Pulau Lang Tengah, which is a completely different island.

Travel agencies, bus companies and ferry terminals weren’t much help either. I asked just about everyone I encountered in Malaysia if they could tell me how to get to Pulau Tengah. As was the case online, the locals would tell me how to get to Pulau Lang Tengah instead.

I started to doubt myself. Perhaps Pulau Tengah and Pulau Lang Tengah were indeed the same island?

I checked in with my dad several times over email. “Are you suuuure it was Pulau Tengah, and not Pulau Lang Tengah?”

It absolutely, positively was Pulau Tengah. Dad was certain of this. Pulau Lang Tengah is an island off the northeast coast, and he distinctly recalled being on the southeast coast of Malaysia, near the town of Mersing.

And I was determined to get there.

It was April 13, 2010 when I finally made it. I had just completed my scuba-diving certification in Pulau Tioman, and hopped a boat back to the mainland. By then, I’d gathered enough intel to know for sure that 1) it was definitely “Pulau Tengah” and 2) my ticket there would be through the town of Mersing.

In Mersing, I was told repeatedly that it could not be done. There were no ferries. The island was abandoned. There’s no way to get there. “Impossible,” they told me.

But I wasn’t leaving Malaysia without seeing Pulau Tengah. There had to be a way. With my gigantic backpack in tow, I continued my search. I wandered around and talked to a lot of people, and I hit a lot of dead ends.

But then I met Fairuz Sheikh Ali.

Ms. Ali worked at the Mersing jetty. When I told her I was trying to get to Pulau Tengah, she shook her head immediately and said firmly, “NO BOAT TO TENGAH.”

She did not seem like a woman to be reckoned with.

But I persisted.

“How about Pulau Besar?” I asked if maybe I’d have better luck getting a boat to the larger, neighboring island and going from there. “Can I get a boat to Besar and go to Tengah from there?”

Arms crossed, Ms. Ali blurted out “NO” again, and got a little flustered: “W-WHY you want to go to Tengah?!”

With pleading eyes, I explained that my parents had lived there 32 years ago when it was a Vietnamese refugee camp, and I just wanted to see it.

Ms. Ali softened. She even cracked a warm smile.

She nodded slowly with familiarity. Ms. Ali told me that about a month before me, some other guy – another Vietnamese-American – had come there with a similar story (perhaps it was this guy). And he managed to get to the island.

What?! Really?! I was BEAMING. “Well, how did he GET there?!” A wave of hope washed over me.

“He go on fishing boat.”

YES! I thought. Charter a fishing boat – easy peasy! I was gonna make it to Pulau Tengah after all!

But first, we had to talk money. And I didn’t have on my poker face. (Who am I kidding, I don’t have a poker face.) My excitement to go to Pulau Tengah was impossible to contain. I was smiling uncontrollably from ear to ear and was doing my goofy jump-up-and-down-and clap-my-hands-together-with-excitement thing. I might’ve even hugged her.

In other words, there would be no bargaining power on my end. I was way too excited and I had come a helluva long way to get here. Ms. Ali knew she could throw any number at me and I’d pay it.

“350 ringgit,” she told me. RM350 was about $115 USD at the time. “Cash only.”

I didn’t even blink. I marched straight to town to use the ATM and came back with the money. Total rookie mistake! I should’ve talked her down. (This was my first time in Asia alone; I didn’t learn the art of bargaining until much later.)

Ms. Ali hired a fisherman named Asni to take me to Pulau Tengah and back. I don’t know what his cut of the RM350 was, but I hope it was fair! Asni would be my captain that day, and it would be just him, his boat and me. I left my large backpack behind with Ms. Ali where she would keep it safe and sound until I returned in a few hours.

And off I went with Captain Asni.

The Boat Ride to Pulau Tengah

This was Captain Asni’s boat.

This was Captain Asni.

Captain Asni spoke no English. Absolutely none.

I had many a conversation with him anyway, blabbing his ear off about how much I loved Malaysia, what a journey it’d been to get to this point, and how much Pulau Tengah meant to my family. I repeated the only words I knew in the local language, “terima kasih,” (thank you) over and over.

To fill in awkward silences, I’d rub my belly and start talking about food, because those were the only other words I knew in Malay.

- Mmm, laksa!

- Mmm, nasi lemak!

- Mmm, sambal!

- Mmm, ais kacang!

- Mmm, I love roti canai! Do you like roti canai? My faaaave!

Haha. Awkward much?

Captain Asni was sweet. He’d just smile and nod his head, staring off into the sea. His eyes were terribly bloodshot; he was probably hungover. He’d smoke his cigarette in one hand, steer the boat with the other.

He indulged me with a selfie.

He let me drive for a bit.

And he even did some fishing! (We didn’t catch anything.)

After an hour on the water, Captain Asni pointed straight ahead and said, “Tengah.”

And there it was: Pulau Tengah

My heart leapt. Tears came to my eyes as I caught my first glimpse of Pulau Tengah. My goodness, it was beautiful.

Lush greenery and a forest of palm trees, surrounded by deep blue waters and nothingness. Just this little blob of unassuming land with a brief history that helped change so many people’s lives – in the middle of nowhere.

I sat in silence, bobbing up and down with the rhythm of the waves of the South China Sea. As we got closer and closer to Pulau Tengah, the waters became clear and sparkly. The deep blue turned into a vibrant turquoise. It was paradise.

My PARENTS were here once, I thought. They had just left behind their families, their friends, their country, their entire LIVES at a moment’s notice. And they came HERE. They found safety here. They found hope here. They were able to move to the US and live the American dream because they came here.

HERE!

I was overwhelmed.

There was nowhere to dock the boat. This meant a wet landing. At this point in my travels, I’d gotten used to wet landings – climbing out of the boat directly into the water and wading into shore on foot. But usually it was up to the shins; at worst, just above the knees. At Pulau Tengah, Captain Asni was only able to get the boat close enough to shore that I’d have to disembark into the water almost all the way up to my neck. Good thing I had on my swimsuit!

Here’s Captain Asni showing me how it’s done!

I climbed over the side of the boat and hopped into the water. The water was warm. And it was clear. So clear, I was up to my chest in it and could look down and see my toes as if on HDTV. I reached up towards the boat for the captain to hand me my small daypack. I carried the bag over my head and started wading towards shore.

Captain Asni stayed behind on the boat. Between his version of weird sign language and mine, we communicated to each other that he would be within eyeshot while I was on the island and that I would just wave from shore when I was ready to go. Okie dokie then.

What did I do on Pulau Tengah?

As I waded onto shore, I looked around. There was absolutely no trace of the refugee camp.

There was sand. There were palm trees. Vegetation. Some rocks.

It was exactly how one imagines being stranded on a tropical island. It was just a little blob of land…and little old backpacker me.

I stood there all alone with the sand between my toes, the hot sun beating down on me, and I took it all in. I imagined my parents approaching this island on their stolen Vietnamese boat, wading in just as I had just done – but instead of the silence that welcomed me, I imagined being excitedly greeted by hundreds of fellow freedom-seeking refugees, hoping this new arrival meant a reunion with a loved one. Everyone had hopes and dreams about what their futures looked like, but no one really knew. Would they be on this island a few days? Months? Years? Forever?

But these weren’t my memories. These were my parents’ memories. My Aunt Hai’s memories, my Uncle Côi’s memories, my cousins’ memories. They’re the ones who left behind everything they knew and stood on this very same sand with only the clothes on their backs and hope for a better life. This place had so many stories. I could only imagine it. My parents lived it. I wished they were there with me. Tears started to wet my lashes and I got a bit choked up.

The good fortune I had to be standing there was not lost on me.

And then I felt my feet catch on fire. Yeah, my feet. FIRE. Figuratively speaking, of course. That sand was HOT! Haha. I scrambled to put on my flip flops, shook off my tears, and I went exploring.

My dad had emailed me a photo of him on the island 32 years earlier, and I tried to find the exact location it was taken. Here’s the best I could do (that’s dad on the far right):

1978

2010

Hmm, what…else…could I dooo on Pulau Tengah?

I could jump in the water and go for a nice swim? Sure. And I did for a bit. But I’d also just spent three days scuba-diving, so I was a bit swimmed out.

I could just lay out my sarong and sunbathe? I could. But I was getting attacked by sandflies. Like, in a baaaad way. Those of you who know tropical sandflies – they’re awful, right?! Worse than mosquitoes! Pictured here is my lumpy, itchy, scabby, sandfly-bitten arm one week later in Bali.

Besides getting eaten alive by sandflies, there was really nothing to do on Pulau Tengah but walk around and explore. I climbed up and over a lot of large rocks, weaved my way through and around some thick vegetation. I took some photos.

Occasionally, I’d look back to make sure Captain Asni hadn’t passed out and drifted off to sea without me. There’s his boat in the distance:

Some areas I couldn’t reach on foot because the tide was too high. A few times, I flagged down Captain Asni to pick me up and drop me off on other parts of the island. This was tricky too, as we had to make sure to avoid coral reefs. There weren’t a lot of places for a boat that size to access the beaches.

I did two more hop-offs on different parts of the island before I spotted these two guys. I wasn’t alone on Pulau Tengah after all!

These fishermen were relaxing in makeshift hammocks when I walked up and attempted a conversation. They didn’t speak much English, and it didn’t seem fitting to rattle off all my favorite Malaysian foods as I had with Captain Asni. So it was mostly just a lot of staring and smiling and sheepishly throwing out random phrases in our respective languages. I probably said something dumb like, “Beautiful day!” or “Nice hammock!”

The friendly one, Min, broke the awkwardness by pointing out a large scrape on my leg. It was a really fresh wound. In my climbing of rocks and trudging through brush around the island, I’d fallen many times. The scrape was a good five inches long, inch and a half wide, with a trace amount of blood. I hadn’t even noticed! Min grabbed an ointment out of his bag for me. No idea what it was, but I applied it anyway.

Back on the boat, Captain Asni and I circled the island. On the south side, I could see there’d been an attempt to build a resort or something, but it appeared abandoned when I was there. I’ve since found out that the resort was actually completed, opening two years later in April 2012. It’s called Batu Batu Resort:

Captain Asni then weaved us around the surrounding islands – Pulau Hujong to the north; Pulau Besar to the south. The resort island of Pulau Rawa was in the distance to the northeast.

We did a little more fishing (still caught nothing). Then we headed back to Mersing.

Here’s me, leaving Pulau Tengah and feeling very satisfied.

The whole thing took about four hours and it was plenty of time. Pulau Tengah had literally nothing to offer as a travel destination at the time, but that’s not what I was looking for. I went to Pulau Tengah in honor of my parents and the journey they made to find a better life. I was stoked just to set foot on the island!

I do wish I had collected some sand or a small rock though. Would’ve loved to bring something back to my parents from Pulau Tengah. Oh well. Coulda shoulda woulda. Maybe we’ll come back and check out that new Batu Batu Resort.

The experience itself was unforgettable. I’m terribly grateful for the opportunity to see Pulau Tengah with my own eyes. But most importantly, I’m grateful for the dialogue it’s opened up between my parents and me about their journey to America.

It’s because they fled their home country that I got to grow up with relative freedom – a freedom they could only dream of in post-war Vietnam. The risks they took, the sacrifices they made, the lives they’ve built for themselves and for my siblings and me…I am profoundly grateful.

Thanks Mom! Thanks Dad! And thank you to Uncle Côi and Aunt Hai!

—–

My parents’ story was featured in The Seattle Times today! Read it here: Vietnamese Couple Recount Harrowing Escape to Land They Embrace

For more Vietnamese refugee stories, check out:

- Returning to Pulau Tengah: A fellow Vietnamese-American world traveler who also journeyed to Pulau Tengah, years after he himself was on the island as a refugee baby.

- Last Days in Vietnam: The Oscar-nominated documentary with incredible stories and footage of the day Saigon fell. (So riveting, I’ve seen it three times.)

- After the fall of Saigon: When Washington did the right thing for refugees: A Seattle Times editorial tribute to former Governor Dan Evans who played a pivotal role in bringing refugees to Washington state.

Wonderful, heart-felt personal story that could only be told by someone as talented as Thy. 🙂 Thank you for taking the time to share your parent’s amazing journey with the rest of us and now it will be forever captured.

Thank you love! I learned so much while writing this piece, and the process inspired so many great conversations with my parents. Going to Pulau Tengah was unforgettable!

I am in the boat Con Dao 3′ teach English in the camp tengah. I am one of the member organized the boat out of Cantho. I am living in Minnesota for over 35 years. Email to me if your parent still remember me. Thank you.

Vinh, wow, thank you so much for reaching out! My parents would love to get in touch with fellow refugees from the Con Dao 3. I’ll have them email you!

J’étais à PULAU TENGAH en 1978. Connaîtriez vous un garçon qui s’appelle NGUYEN Huu Tri qui y était aussi 1978. Il avait environ 24 ans. Il s’occupait sur l’ile de l’électricité. Je sais qu’il était venu d’une province du VN et non de VUNG TAU, mais j’oublie de quelle province. Il jouait aussi de la guitare sur l’île. Il est venu au tout début en FLORIDA (USA) vers 1979, puis OKLAHOMA et dernière adresse connue à LOS ANGELES. Je suis joignable à l’adresse “dupontloan@msn.com”.

I will pass this information along to my parents and see if they remember anyone by that name!

Merci. Je crois qu’il y a un membre qui s’appelle Donovan Lê dont le père le connaissait puisqu’il avait pris sa suite après le départ de Tri aux USA pour s’occuper du générateur sur l’île…. mais après 40 ans … chercher quelqu’un c’est comme chercher une aiguille dans une botte de foin..!!

Indeed!

Thank you Thy for writing this great piece. I enjoyed reading it very much. I was given this website and article by my sister who got it from my cousin. Long story short. My family was also on the Con Dao 3 and i didnt know that this island could be found. I wish you and your family all the best and hope you continue to write and travel and do great things. Peace. Love. And pho.

Thanks for writing Huy! It’s so neat to get in touch with others who experienced the Con Dao 3 and Pulau Tengah with my parents. It makes their story that much more real and more alive to me, if that makes any sense. I’ll be reaching out via email. Peace, love and pho to you too, ha!

Hello Thy, I love your story visited Tengah. I was 15 yrs old boy in Pulau Tengah with my older brother who was 17 at the time. I was there from May 1978 to March 1979 before settled in North Carolina. I don’t remember my boat number but I left Can Tho, VN in 4/30/78 and made to Tengah in May 78. Again, thank you for your story.

Hi Yung! You and your brother were likely on the island with my parents for some of that time. And you guys were around my mother’s age too! I hope NC has been good to you. Thank you for reaching out!

Hello Pulau! One of my dearest, best friends (Ngoc Nguyen) shared your story with me. Her family was on the boat/island with your family. I never knew this story- I read it on a plane and it made me weep- and laugh out loud. Thank you for sharing this history lesson and for making your brave journey “home!” Love, nej

Nej, it’s my pleasure to share this story. I’m so glad you enjoyed it!

“But I persisted.

“How about Pulau Besar?” I asked if maybe I’d have better luck getting a boat to the larger, neighboring island and going from there. “Can I get a boat to Besar and go to Tengah from there?”

Arms crossed, Ms. Ali blurted out “NO” again, and got a little flustered: “W-WHY you want to go to Tengah?!”

With pleading eyes, I explained that my parents had lived there 32 years ago when it was a Vietnamese refugee camp, and I just wanted to see it.”

Chú thích đoạn này, chú cũng ở trong tình cảnh này.

I’m so glad you enjoyed it. Cảm ơn nhiều 🙂

What a great read! My family stayed there in 1979. My dad took over running the generator for the island after his friend left. We lived right next to the church in Trung Dao. I am planning to bring my wife and kids back within the next couple of years.

Donovan, I bet your dad has amazing stories! What a special place Pulau Tengah has in the hearts of so many people with so many different stories. Going there will be such a special experience for you and your family. I’d love to hear about it someday. Best wishes to you all!

Votre père a pris le relais pour faire fonctionner le générateur après le départ de son ami? Quel est le nom de son ami? Est ce bien NGUYEN Huu Tri ? Il avait à l’époque environ 24 ans , s’occupait du générateur et avait quitté PULAU TENGAH en 1979 pour Florida, puis OKLAHOMA puis dernière adresse connue à LOS ANGELES. mail ; dupontloan@msn.com

Dear Thy,

Thank you for showing the pictures of Pulau-Tengah Refugee Camp. I have many flashbacks from time to time about my freedom journey at this camp in 1979. My boat was headed out from Ca-Mau, and I think the boat number is MH-1300 or MH-1700 ,not sure of which. Memories left there from year to year and miles and miles away. I am shocked and trembling to read up your hunting story of your parents’ footsteps, and see those shelters shown in the picture with a woman, girl and a boy – That I see the shelter where I used to live. – lonely and hopelessness in the island. My hometown was Can-Tho where your parents’ departed origin escape place. There many escape people got caught and were jailed likely too.

The island is a paradise place to settle many Vietnamese refugees in search of freedom. I recall many things during my ordeal that I have to be strong to confront a real life first time in my life leaving behind my parents and siblings.

I am grateful for your story, and am sure today many Vietnamese refugees still clinging on those hardship ordeal and memories that they have had left behind there for their generations to come to remember and to appreciate of their upbringing today in human history. Thank you so much, Thy.

I’m so moved by your story, Lam, thank you for sharing! I hope you’ve found healing and strength in the memory of your journey through Pulau Tengah. You, like so many refugees, are an inspiration to me. Best wishes to you, and chúc mừng năm mới!

This is amazing- Thank you for sharing. I’ve been trying to chronicle information from my parents escape around the same time. In fact just months apart from your parents. I saw that your parents have the same refugee card as my dad. My dad has left later so I think by that time they paid the VC 10 ounces of gold to leave from Vung Tau.

Hi Jen! Thank you for writing. It’s amazing to see those refugee cards, isn’t it! What a journey to chronicle the stories of our parents’ generation – I hope it’s been a meaningful experience for you and your family. Every story is important and every story should be told.

Hi Thy,

As I got older I think about the time I spent on that island more, not sure why.

I was there from July 1979- July 1980. I was 15 at the time, no family, all by myself with my cousin who was 16. She left to US months before I did.

I came back and worked in Malaysia in 1997 and visited this island with some co-workers.

The sea water got most of the island… it looked quite different from I what remember…,

Sometimes, I wonder what happens to all the people whom I met and hung out when I was a refugee there…

I am glad you have a chance to see part of the history of the boat people.

I plan to take my family there next year and show my daughter what I went thru when I was at her age.

Thank you for all the beautiful pictures

An Nguyen (Boat# MT056)

Hi An, I’m replying quite late here, sorry about that. Thank you for writing. I’m fascinated by your story! You weren’t much younger than my mom was when she was on Pulau Tengah, but she had a lot of family with her – I can’t imagine what it was like for you to be so young and so alone. I’d love to hear more about your story and if you got to take your family back there!

I am in the process of writing a book with my wife and family who lived on the island for 2 years. Is it possible to use some of your photos and cite them? They saved absolutely no photos from that time. I read your post and it’s really great.

Hi Robert, I’m so sorry for the late reply. Thank you for reaching out! Yes, please feel free to use and cite my photos. Not all of them are mine but those references are cited above. Email me at travelingthy@gmail.com if you need more details. I’d love to hear about your book!